Astronomers using a new method to find small planets orbiting nearby stars, which previous surveys had overlooked, discovered 18 Earth-sized exoplanets.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), the Georg August University of Göttingen, and the Sonneberg Observatory have discovered 18 Earth-sized planets beyond the solar system. The worlds are so small that previous surveys had overlooked them. One of them is one of the smallest known so far; another one could offer conditions friendly to life. The researchers re-analyzed a part of the data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope with a new and more sensitive method that they developed. The team estimates that their new method has the potential of finding more than 100 additional exoplanets in the Kepler mission’s entire data set. The scientists describe their results in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Somewhat more than 4000 planets orbiting stars outside our solar system are known so far.

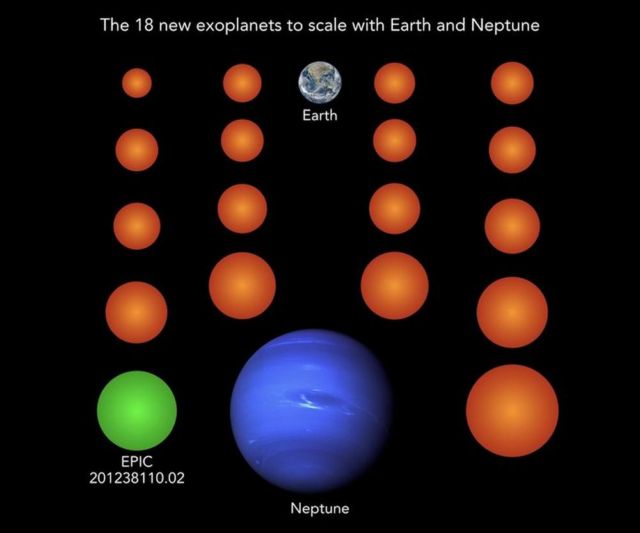

Of these so-called exoplanets, about 96 percent are significantly larger than our Earth, most of them more comparable with the dimensions of the gas giants Neptune or Jupiter. This percentage likely does not reflect the real conditions in space, however, since small planets are much harder to track down than big ones. Moreover, small worlds are fascinating targets in the search for Earth-like, potentially habitable planets outside the solar system.

The 18 newly discovered worlds fall into the category of Earth-sized planets. The smallest of them is only 69 percent of the size of the Earth; the largest is barely more than twice the Earth’s radius. And they have another thing in common: all 18 planets could not be detected in the data from the Kepler Space Telescope so far. Common search algorithms were not sensitive enough.

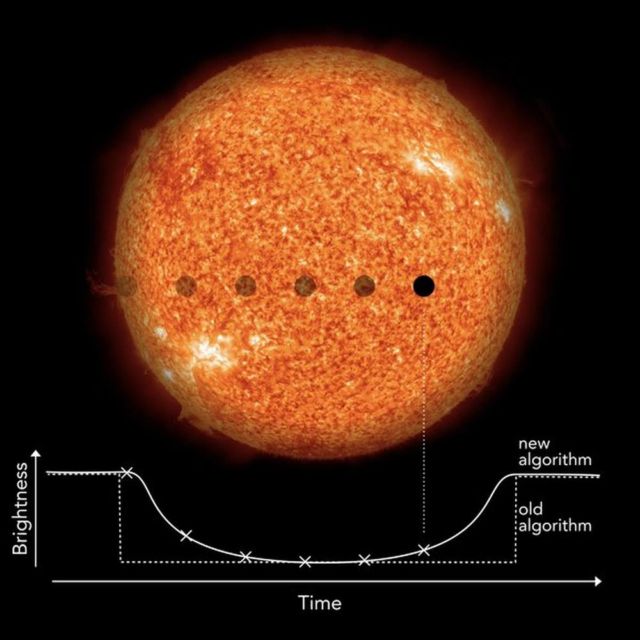

In their search for distant worlds, scientists often use the so-called transit method to look for stars with periodically recurring drops in brightness. If a star happens to have a planet whose orbital plane is aligned with the line of sight from Earth, the planet occults a small fraction of the stellar light as it passes in front of the star once per orbit.

“Standard search algorithms attempt to identify sudden drops in brightness,” explains Dr. René Heller from MPS, first author of the current publications. “In reality, however, a stellar disk appears slightly darker at the edge than in the center. When a planet moves in front of a star, it therefore initially blocks less starlight than at the mid-time of the transit. The maximum dimming of the star occurs in the center of the transit just before the star becomes gradually brighter again,” he explains.

More at Max Planck Institute

Leave A Comment