UCLA scientists created thermoelectric coolers that are only one ten-millionth of a meter.

A team led by UCLA physics professor Chris Regan has succeeded in creating thermoelectric coolers that are only 100 nanometers thick — roughly one ten-millionth of a meter — and have developed an innovative new technique for measuring their cooling performance.

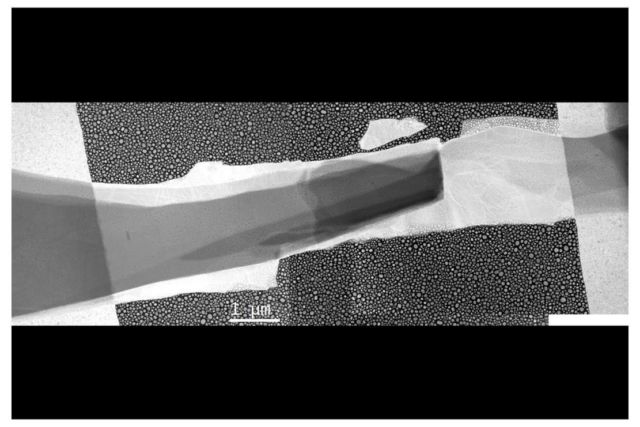

Above: This electron microscope image shows the cooler’s two semiconductors — one flake of bismuth telluride and one of antimony-bismuth telluride — overlapping at the dark area in the middle, which is where most of the cooling occurs. The small “dots” are indium nanoparticles, which the team used as thermometers. Credit UCLA/Regan Group

“We have made the world’s smallest refrigerator,” said Regan, the lead author of a paper on the research published recently in the journal ACS Nano.

To be clear, these miniscule devices aren’t refrigerators in the everyday sense — there are no doors or crisper drawers. But at larger scales, the same technology is used to cool computers and other electronic devices, to regulate temperature in fiber-optic networks, and to reduce image “noise” in high-end telescopes and digital cameras.

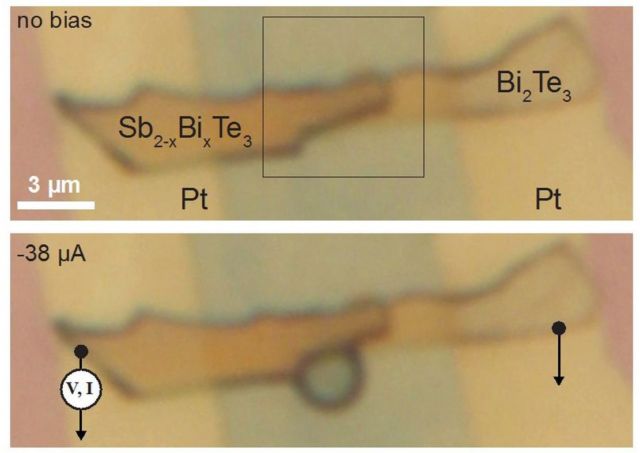

As the thermoelectric cooler becomes cold, a dewdrop (green) forms where the device’s two semiconducting materials overlap. Credit UCLA/Regan Group

Made by sandwiching two different semiconductors between metalized plates, these devices work in two ways. When heat is applied, one side becomes hot and the other remains cool; that temperature difference can be used to generate electricity. The scientific instruments on NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, for instance, have been powered for 40 years by electricity from thermoelectric devices wrapped around heat-producing plutonium. In the future, similar devices might be used to help capture heat from your car’s exhaust to power its air conditioner.

source UCLA

Leave A Comment