A 210,000-year-old skull in Mani, Greece, discovered, the oldest example of a modern man in Eurasia.

Universities of Tübingen and Athens archeologist identify 210,000-year old modern human skull, in Greece, the earliest known Homo sapiens in Eurasia.

Early modern humans left Africa earlier than previously assumed, reaching Europe nearly 150,000 years earlier than previously known, indicates research led by the Universities of Tübingen and Athens. After comprehensive analyses, scientists identified a skull from the Apidima site, southern Greece, as early Homo sapiens and dated it to about 210,000 years ago. This makes it the earliest modern human known outside Africa, says the international team led by Professor Katerina Harvati from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen.

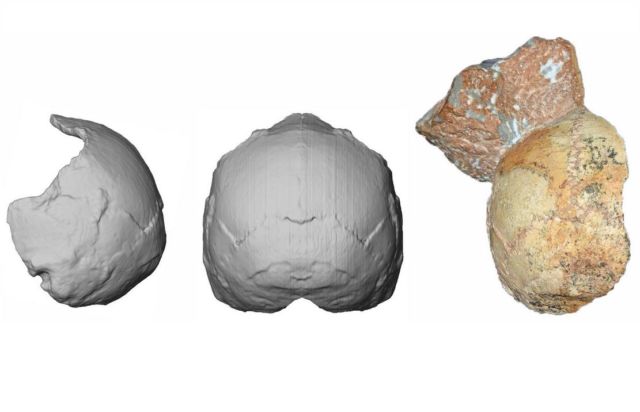

Above, the partial skull (right), its virtual reconstruction (middle) and a virtual side view. Image credit Katerina Harvati/Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen

From the Press release:

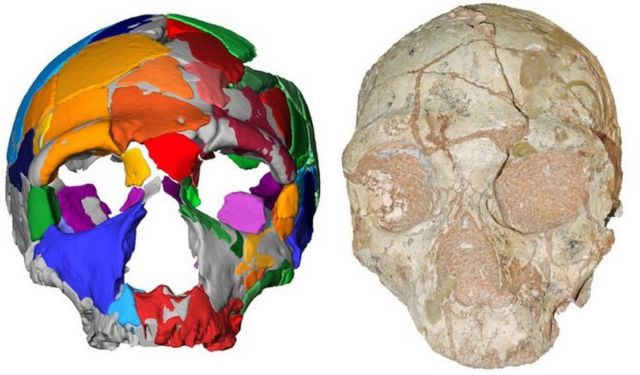

The fossil find, Apidima 1, originates from the site of Apidima, southern Greece and was found together with another human fossil, Apidima 2, during research by the Museum of Anthropology of the University of Athens in the late 1970s. The research team applied novel, cutting edge approaches, including virtual reconstructions of the damaged parts of the skulls. It conducted numerous comparisons with different human fossils, and used a highly accurate radiometric dating method to determine their age. “Apidima 2 is about 170,000 years old. We could tell that it was a Neanderthal,” says Katerina Harvati. “Surprisingly, Apidima 1 is even older, about 210,000 years old, but has no Neanderthal features.” Rather, the study revealed a mixture of modern human and archaic characteristics, indicating an early Homo sapiens.

“Our results suggest that at least two groups of people lived in the Middle Pleistocene in what is now southern Greece: an early population of Homo sapiens and, later, a group of Neanderthals,” says Harvati. This supports the hypothesis that early modern humans spread out of Africa, where they evolved, multiple times. “The Apidima 1 skull shows an early dispersal happened earlier than we thought, and also reached further geographically, into Europe itself.” Apidima 1 is more than 150 thousand years older than the oldest modern human specimens known from Europe until now.

The Apidima 2 cranium (right) and its reconstruction (left). Apidima 2 shows a suite of features characteristic of Neanderthals, indicating that it belongs to the Neanderthal lineage. Image credit Katerina Harvati/Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen

“We hypothesize that, as in the Near East, the early modern human population represented by Apidima 1 was probably replaced by Neanderthals, whose presence in southern Greece is well documented, including by the Apidima 2 skull from the same site,” says Harvati, outlining what appears to have happened. But Neanderthals also had to make way. In the late Palaeolithic, some 40,000 years ago, newly-arrived modern humans settled in the region, as in the rest of Europe. Their presence is documented by finely-worked stone tools and other finds. Neanderthals became extinct around this time. “This discovery highlights the importance of Southeast Europe for human evolution “, concludes Harvati.

The Apidima cave was excavated in the 1970s and -80s by the Museum of Anthropology of the Medical School of the University of Athens. The Museum was founded in 1886, and is one of the earliest of its kind in Europe. It has played an important role, not only in research ‒ most notably the excavations at Apidima ‒ but also in educating the public.

The researchers plan further studies of the Apidima material, long considered important for human evolution, but shown to be of even greater significance by the new results. “The Museum of Anthropology houses these important finding from our excavations of the Apidima site. This publication is the first in a series of detailed studies that we plan in collaboration with the team of Prof. Harvati” says Professor Kouloukoussa, the Museum’s director. Professor Gorgoulis, head of the Department of Histology and Embryology at the University of Athens, adds “This is another example of the University of Athens’ cutting edge research. We are very happy that these findings are now receiving international recognition, resulting from the successful collaborative research led by our institutions.”

The study was published in the journal Nature.

source Tuebingen University

Leave A Comment