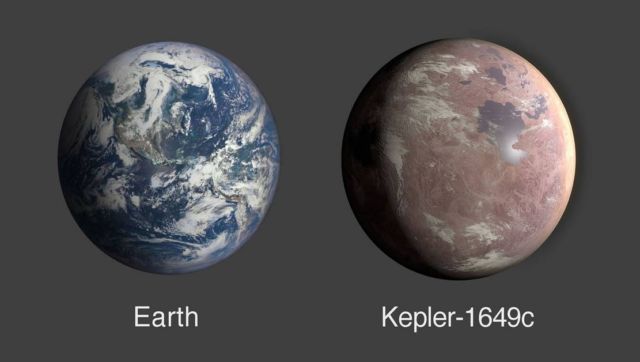

The most Earth-like exoplanet discovered, 300 light-years away, orbiting in the habitable zone of its star., hidden in early NASA Kepler data.

Kepler-1649c is 1.06 times larger than Earth, has similar surface temperature and is orbiting a red dwarf star every 19.5 days.

It was found by the NASA Kepler space telescope in 2013, but had been ‘mislabelled’ by automated tools.

Above: A comparison of Earth and Kepler-1649c, an exoplanet only 1.06 times Earth’s radius. Credits: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter

Top image: An illustration of Kepler-1649c orbiting around its host red dwarf star. This newly discovered exoplanet is in its star’s habitable zone and is the closest to Earth in size and temperature found yet in Kepler’s data. Credits: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter

A team of transatlantic scientists, using reanalyzed data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope, has discovered an Earth-size exoplanet orbiting in its star’s habitable zone, the area around a star where a rocky planet could support liquid water.

Scientists discovered this planet, called Kepler-1649c, when looking through old observations from Kepler, which the agency retired in 2018. While previous searches with a computer algorithm misidentified it, researchers reviewing Kepler data took a second look at the signature and recognized it as a planet. Out of all the exoplanets found by Kepler, this distant world – located 300 light-years from Earth – is most similar to Earth in size and estimated temperature.

An illustration of what Kepler-1649c could look like from its surface.

Credits: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter

Most of the time, those dips come from phenomena other than planets – ranging from natural changes in a star’s brightness to other cosmic objects passing by – making it look like a planet is there when it’s not. Robovetter’s job was to distinguish the 12% of dips that were real planets. Those signatures Robovetter determined to be from other sources were labeled “false positives,” the term for a test result mistakenly classified as positive.

With an enormous number of tricky signals, astronomers knew the algorithm would make mistakes and would need to be double-checked – a perfect job for the Kepler False Positive Working Group. That team reviews Robovetter’s work, going through all false positives to ensure they are truly errors and not exoplanets, ensuring fewer potential discoveries are overlooked. As it turns out, Robovetter had mislabeled Kepler-1649c.

Most of the time, those dips come from phenomena other than planets – ranging from natural changes in a star’s brightness to other cosmic objects passing by – making it look like a planet is there when it’s not. Robovetter’s job was to distinguish the 12% of dips that were real planets. Those signatures Robovetter determined to be from other sources were labeled “false positives,” the term for a test result mistakenly classified as positive.

With an enormous number of tricky signals, astronomers knew the algorithm would make mistakes and would need to be double-checked – a perfect job for the Kepler False Positive Working Group. That team reviews Robovetter’s work, going through all false positives to ensure they are truly errors and not exoplanets, ensuring fewer potential discoveries are overlooked. As it turns out, Robovetter had mislabeled Kepler-1649c.

This newly revealed world is only 1.06 times larger than our own planet. Also, the amount of starlight it receives from its host star is 75% of the amount of light Earth receives from our Sun – meaning the exoplanet’s temperature may be similar to our planet’s, as well. But unlike Earth, it orbits a red dwarf. Though none have been observed in this system, this type of star is known for stellar flare-ups that may make a planet’s environment challenging for any potential life.

“This intriguing, distant world gives us even greater hope that a second Earth lies among the stars, waiting to be found,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “The data gathered by missions like Kepler and our Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will continue to yield amazing discoveries as the science community refines its abilities to look for promising planets year after year.”

source NASA

Leave A Comment