New research by engineers at MIT could lead to batteries that can pack more power per pound and last longer.

The new electrode concept comes from the laboratory of Ju Li, the Battelle Energy Alliance Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering and professor of materials science and engineering. It is described today in the journal Nature, in a paper co-authored by Yuming Chen and Ziqiang Wang at MIT, along with 11 others at MIT and in Hong Kong, Florida, and Texas.

The design is part of a concept for developing safe all-solid-state batteries, dispensing with the liquid or polymer gel usually used as the electrolyte material between the battery’s two electrodes. An electrolyte allows lithium ions to travel back and forth during the charging and discharging cycles of the battery, and an all-solid version could be safer than liquid electrolytes, which have high volatilility and have been the source of explosions in lithium batteries.

“There has been a lot of work on solid-state batteries, with lithium metal electrodes and solid electrolytes,” Li says, but these efforts have faced a number of issues.

One of the biggest problems is that when the battery is charged up, atoms accumulate inside the lithium metal, causing it to expand. The metal then shrinks again during discharge, as the battery is used. These repeated changes in the metal’s dimensions, somewhat like the process of inhaling and exhaling, make it difficult for the solids to maintain constant contact, and tend to cause the solid electrolyte to fracture or detach.

Another problem is that none of the proposed solid electrolytes are truly chemically stable while in contact with the highly reactive lithium metal, and they tend to degrade over time.

Most attempts to overcome these problems have focused on designing solid electrolyte materials that are absolutely stable against lithium metal, which turns out to be difficult. Instead, Li and his team adopted an unusual design that utilizes two additional classes of solids, “mixed ionic-electronic conductors” (MIEC) and “electron and Li-ion insulators” (ELI), which are absolutely chemically stable in contact with lithium metal.

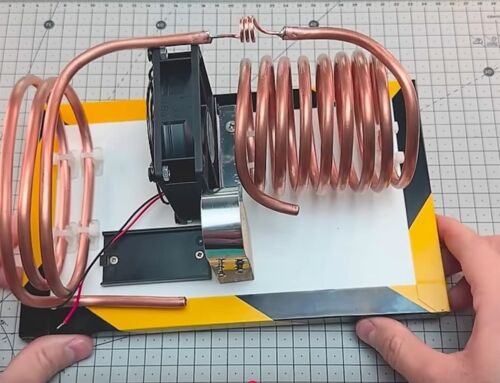

The researchers developed a three-dimensional nanoarchitecture in the form of a honeycomb-like array of hexagonal MIEC tubes, partially infused with the solid lithium metal to form one electrode of the battery, but with extra space left inside each tube. When the lithium expands in the charging process, it flows into the empty space in the interior of the tubes, moving like a liquid even though it retains its solid crystalline structure. This flow, entirely confined inside the honeycomb structure, relieves the pressure from the expansion caused by charging, but without changing the electrode’s outer dimensions or the boundary between the electrode and electrolyte. The other material, the ELI, serves as a crucial mechanical binder between the MIEC walls and the solid electrolyte layer.

“We designed this structure that gives us three-dimensional electrodes, like a honeycomb,” Li says. The void spaces in each tube of the structure allow the lithium to “creep backward” into the tubes, “and that way, it doesn’t build up stress to crack the solid electrolyte.” The expanding and contracting lithium inside these tubes moves in and out, sort of like a car engine’s pistons inside their cylinders. Because these structures are built at nanoscale dimensions (the tubes are about 100 to 300 nanometers in diameter, and tens of microns in height), the result is like “an engine with 10 billion pistons, with lithium metal as the working fluid,” Li says.

Because the walls of these honeycomb-like structures are made of chemically stable MIEC, the lithium never loses electrical contact with the material, Li says. Thus, the whole solid battery can remain mechanically and chemically stable as it goes through its cycles of use. The team has proved the concept experimentally, putting a test device through 100 cycles of charging and discharging without producing any fracturing of the solids.

source MIT

I take my hat off to these scientists for the many hours, days, months, & years that they dedicate to these tasks. Batteries have changed so much in the last hundred years it is beyond comprehension.