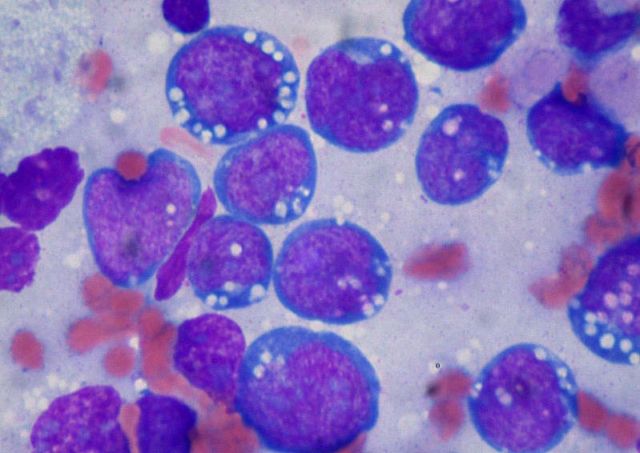

Stanford researchers have found that cancer cells have a protein called CD24 on their surface that enables them to protect themselves against the body’s immune cells.

Cancer cells are known to protect themselves using proteins that tell immune cells not to attack them. Stanford researchers have discovered a new “don’t eat me” signal, and blocking it may make cancer cells vulnerable to attack by the immune system.

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered a new signal that cancers seem to use to evade detection and destruction by the immune system.

The scientists have shown that blocking this signal in mice implanted with human cancers allows immune cells to attack the cancers. Blocking other “don’t eat me” signals has become the basis for other possible anti-cancer therapies.

Normally, immune cells called macrophages will detect cancer cells, then engulf and devour them. In recent years, researchers have discovered that proteins on the cell surface can tell macrophages not to eat and destroy them. This can be useful to help normal cells keep the immune system from attacking them, but cancer cells use these “don’t eat me” signals to hide from the immune system.

The researchers had previously shown that the proteins PD-L1, CD47 and the beta-2-microglobulin subunit of the major histocompatibility class 1 complex, are all used by cancer cells to protect themselves from immune cells. Antibodies that block CD47 are in clinical trials. Cancer treatments that target PD-L1 or the PDL1 receptor are being used in the clinic.

The Stanford researchers now report they have found that a protein called CD24 also acts as a “don’t eat me” signal and is used by cancer cells to protect themselves.

A paper describing the research was published July 31 in Nature. Amira Barkal, an MD-PhD student, is the lead author. Irving Weissman, MD, professor of pathology and of developmental biology and director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine and director of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Stem Cell Research, is the senior author.

“Finding that not all patients responded to anti-CD47 antibodies helped fuel our research at Stanford to test whether non-responder cells and patients might have alternative ‘don’t eat me’ signals,” said Weissman, who holds the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professorship for Clinical Investigation in Cancer Research.

source Stanford University

Leave A Comment