Scientists find that some sperms poison their competitors to reach the egg cell first.

Competition among sperm cells is fierce – they all want to reach the egg cell first to fertilize it.

A research team from Berlin now shows in mice that the ability of sperm to move progressively depends on the protein RAC1. Optimal amounts of active protein improve the competitiveness of individual sperm, whereas aberrant activity can cause male infertility.

It is literally a race for life when millions of sperm swim towards the egg cells to fertilize them. But does pure luck decide which sperm succeeds? As it turns out, there are differences in competitiveness between individual sperm. In mice, a “selfish” and naturally occurring DNA segment breaks the standard rules of genetic inheritance – and awards a success rate of up to 99 percent to sperm cells containing it.

A team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin describes how the genetic factor called “t-haplotype” promotes the fertilization success of sperm carrying it.

The researchers for the first time showed experimentally that sperm with the t-haplotype are more progressive, i.e., move faster forward than their “normal” peers, and thereby establish their advantage in fertilization.

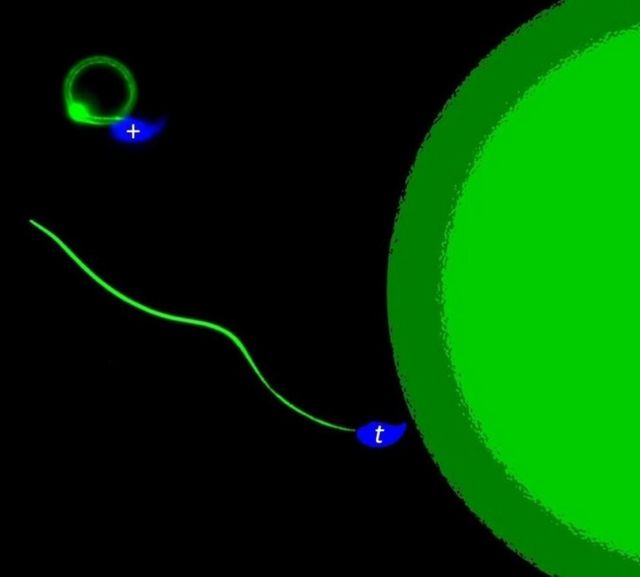

In direct competition, t-sperm outcompete their normal peers (+) in the race for the egg cell with genetic tricks, letting them swim in circles. Credit MPI f. Molecular Genetics/ Alexandra Amaral

In direct competition, t-sperm outcompete their normal peers (+) in the race for the egg cell with genetic tricks, letting them swim in circles. Credit MPI f. Molecular Genetics/ Alexandra Amaral

Most importantly, they linked the differences in motility to the molecule RAC1. This molecular switch transmits signals from outside the cell to the inside by activating other proteins. The molecule is known to be involved in directing e.g., white blood cells or cancer cells towards cells exuding chemical signals. The new data suggest that RAC1 might also play a role in directing sperm cells towards the egg, “sniffing” their way to their target.

“The competitiveness of individual sperm seems to depend on an optimal level of active RAC1; both reduced or excessive RAC1 activity interferes with effective forward movement,” says Alexandra Amaral, scientist at the MPIMG and first author of the study.

source Max Planck Institutes

Leave A Comment