Scientists discovered a hydrogen-rich material becoming superconductive under high pressure and at minus 23 degrees Celsius.

Fewer power plants, less greenhouse gases and lower costs: enormous amounts of electricity could be saved if researchers discovered the key to superconductivity at environmental temperatures. Because superconductors are materials that conduct electric energy without losses.

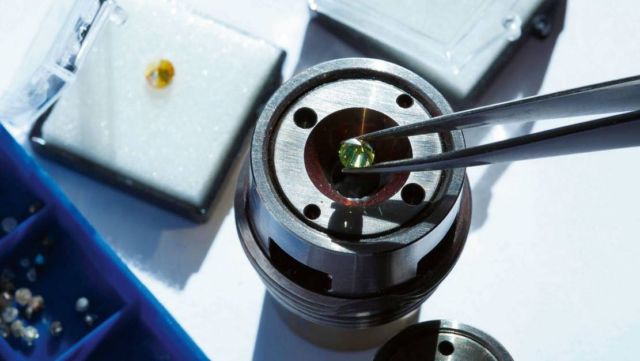

<small\>Above, powerful pressure: in a stamp cell not even the size of a fist, more than a million bar can be produced between two conically ground diamonds, whereby some materials become superconducting at relatively high temperatures. © Thomas Hartmann

A team from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry (MPIC) in Mainz has come a step closer to this goal. The researchers around Mikhail Eremets synthesized lanthanum hydride, a material that shows zero electrical resistance under high pressure at minus 23 degrees Celsius. So far, the record for high-temperature superconductivity was minus 70 degrees Celsius.

“Our study is a major step and milestone on the road to superconductivity at room temperature”, says Eremets, a research group leader at MPIC. For their experiments, the scientists synthesized small amounts of lanthanum hydride (LaH10). In a special chamber only a few hundred cubic microns in size, they exposed the samples to a pressure of 1.7 megabar, which is 1.7 million times the atmospheric pressure, and then cooled them. After reaching the critical temperature of minus 23 degrees Celsius (250 K), the electrical resistance of the samples dropped to zero. Since the superconductivity cannot be clearly demonstrated by resistance measurements alone, the researchers additionally performed measurements in an external magnetic field. A magnetic field disturbs the superconductivity, causing the transition to shift to lower temperatures. That is exactly what the physicists observed.

The high pressure produces metallic lanthanum hydride The latest success builds on major breakthrough that Eremets and colleagues had achieved a few of years ago: they discovered conventional superconductivity in hydrogen sulfide under 2,5 megabar pressure at minus 70 degrees Celsius, which was at much higher temperature than ever observed before. Apparently, hydrogen-rich compounds are capable of superconducting at particularly high temperatures – if they can be brought into a metallic state. In this case the pressure forms the hydride from the metal lanthanum and the hydrogen gas. This is exactly what the high pressure causes.

source Max Planck

Leave A Comment