Scientists say exoplanets circling carbon-rich stars could be made of diamond and silica.

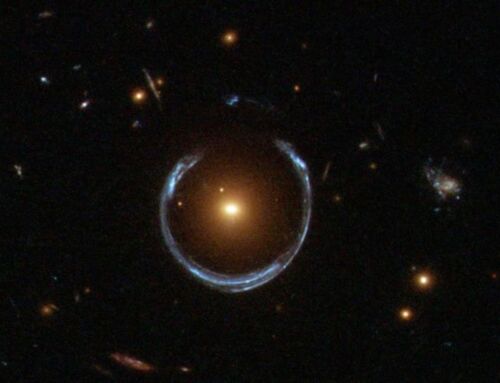

As missions like NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, TESS and Kepler continue to provide insights into the properties of exoplanets (planets around other stars), scientists are increasingly able to piece together what these planets look like, what they are made of and if they could be habitable or even inhabited.

In a new study published recently in The Planetary Science Journal, a team of researchers from Arizona State University and the University of Chicago have determined that some carbon-rich exoplanets, given the right circumstances, could be made of diamonds and silica.

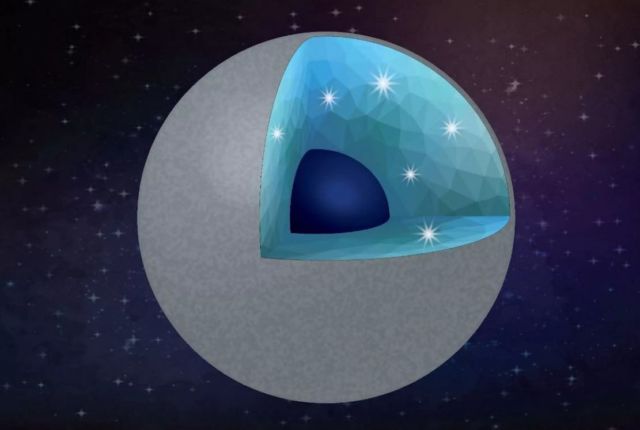

Above: llustration of a carbon-rich planet with diamond and silica as main minerals. Water can convert a carbide planet into a diamond-rich planet. In the interior, the main minerals would be diamond and silica (a layer with crystals in the illustration). The core (dark blue) might be iron-carbon alloy. Credit: Shim/ASU/Vecteezy

“These exoplanets are unlike anything in our solar system,” said lead author Harrison Allen-Sutter of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

When stars and planets are formed, they do so from the same cloud of gas, so their bulk compositions are similar. A star with a lower carbon-to-oxygen ratio will have planets like Earth, comprised of silicates and oxides with a very small diamond content (Earth’s diamond content is about 0.001%).

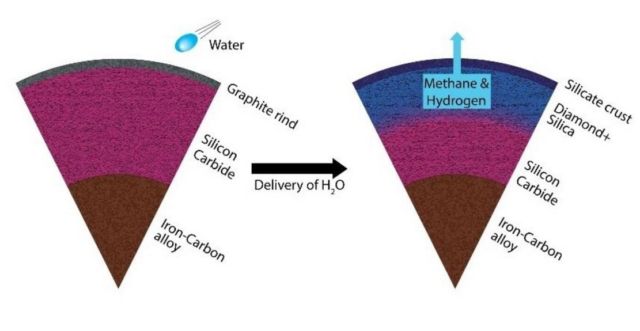

An unaltered carbon planet (left) transforms from a silicon carbide dominated mantle to a silica and diamond dominated mantle (right). The reaction also produces methane and hydrogen. Credit: Harrison/ASU

But exoplanets around stars with a higher carbon-to-oxygen ratio than our sun are more likely to be carbon-rich. Allen-Sutter and co-authors Emily Garhart, Kurt Leinenweber and Dan Shim of ASU, with Vitali Prakapenka and Eran Greenberg of the University of Chicago, hypothesized that these carbon-rich exoplanets could convert to diamond and silicate, if water (which is abundant in the universe) were present, creating a diamond-rich composition.

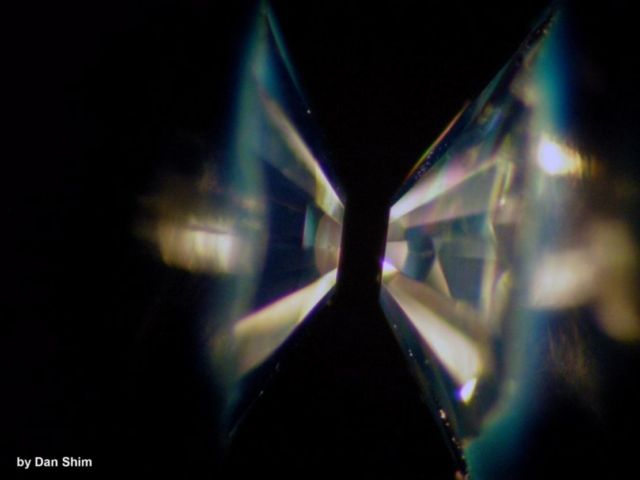

In a diamond-anvil cell, two gem-quality single crystal diamonds are shaped into anvils (flat top in the photo) and then faced towards each other. Samples are loaded between the culets (flat surfaces), then the sample is compressed between the anvils. Credit: Shim/ASU

source Arizona State University

Leave A Comment