Scientists print wearable sensors directly on skin without heat, at room temperature.

An international team of researchers developed a novel technique to produce precise, high-performing biometric sensors.

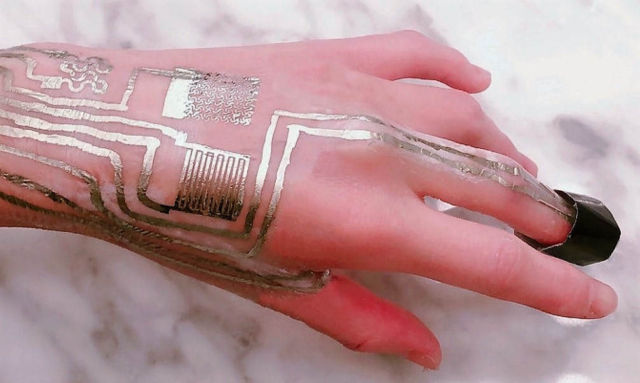

Above: With a novel layer to help the metallic components of the sensor bond, an international team of researchers printed sensors directly on human skin. Credit Ling Zhang, Penn State/Cheng Lab and Harbin Institute of Technology

Wearable sensors are evolving from watches and electrodes to bendable devices that provide far more precise biometric measurements and comfort for users. Now, an international team of researchers has taken the evolution one step further by printing sensors directly on human skin without the use of heat.

Led by Huanyu “Larry” Cheng, Dorothy Quiggle Career Development Professor in the Penn State Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics, the team published their results in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

First author Ling Zhang, a researcher in the Harbin Institute of Technology in China and in Cheng’s laboratory, explains:

“In this article, we report a simple yet universally applicable fabrication technique with the use of a novel sintering aid layer to enable direct printing for on-body sensors.”

Cheng and his colleagues previously developed flexible printed circuit boards for use in wearable sensors, but printing directly on skin has been hindered by the bonding process for the metallic components in the sensor. Called sintering, this process typically requires temperatures of around 572 degrees Fahrenheit (300 degrees Celsius) to bond the sensor’s silver nanoparticles together.

Cheng said:

“The skin surface cannot withstand such a high temperature, obviously. o get around this limitation, we proposed a sintering aid layer — something that would not hurt the skin and could help the material sinter together at a lower temperature.”

By adding a nanoparticle to the mix, the silver particles sinter at a lower temperature of about 212 F (100 C).

Cheng explained, who noted that about 104 F (40 C) could still burn skin tissue:

“That can be used to print sensors on clothing and paper, which is useful, but it’s still higher than we can stand at skin temperature. We changed the formula of the aid layer, changed the printing material and found that we could sinter at room temperature.”

source Penn State University

Leave A Comment