Data from NASA’s Cassini may explain Saturn‘s atmospheric mystery. New mapping of the giant planet’s upper atmosphere reveals likely reason why it’s so hot.

The upper layers in the atmospheres of gas giants – Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune – are hot, just like Earth’s. But unlike Earth, the Sun is too far from these outer planets to account for the high temperatures. Their heat source has been one of the great mysteries of planetary science.

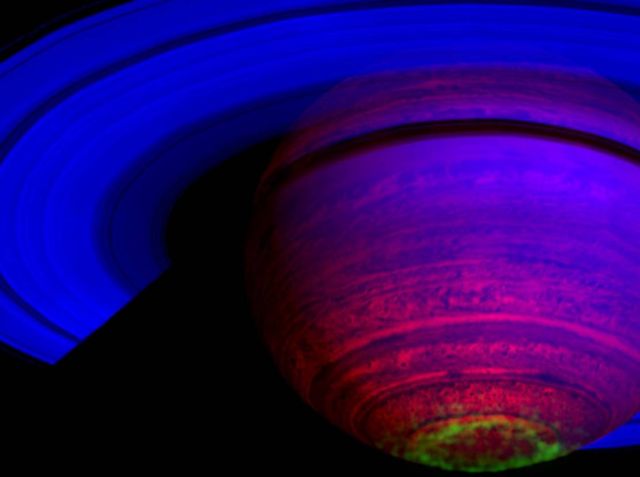

The above false-color composite image shows auroras (depicted in green) above the cloud tops of Saturn’s south pole. The 65 observations used here were captured by Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer on Nov. 1, 2008. Credit: NASA/JPL/ASI/University of Arizona/University of Leicester

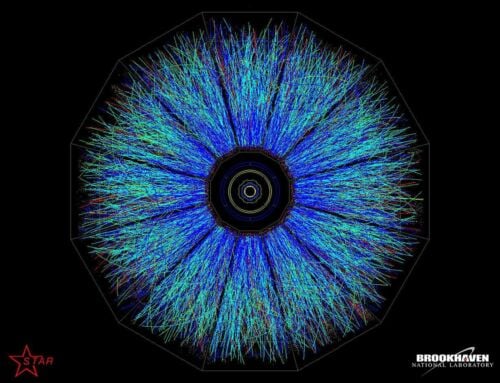

New analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft finds a viable explanation for what’s keeping the upper layers of Saturn, and possibly the other gas giants, so hot: auroras at the planet’s north and south poles. Electric currents, triggered by interactions between solar winds and charged particles from Saturn’s moons, spark the auroras and heat the upper atmosphere. (As with Earth’s northern lights, studying auroras tells scientists what’s going on in the planet’s atmosphere.)

The work, published April 6 in Nature Astronomy, is the most complete mapping yet of both temperature and density of a gas giant’s upper atmosphere – a region that has, in general, been poorly understood.

By building a complete picture of how heat circulates in the atmosphere, scientists are better able to understand how auroral electric currents heat the upper layers of Saturn’s atmosphere and drive winds. The global wind system can distribute this energy, which is initially deposited near the poles toward the equatorial regions, heating them to twice the temperatures expected from the Sun’s heating alone.

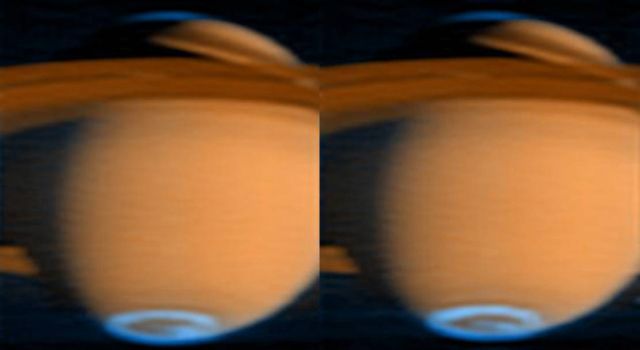

The aurora at Saturn’s southern pole is visible in this false-color image. Blue represents the aurora; red-orange is reflected sunlight. The image was gathered by Cassini’s ultraviolet imaging spectrograph (UVIS) on June 21, 2005. Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Colorado

“The results are vital to our general understanding of planetary upper atmospheres and are an important part of Cassini’s legacy,” said author Tommi Koskinen, a member of Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectograph (UVIS) team. “They help address the question of why the uppermost part of the atmosphere is so hot while the rest of the atmosphere – due to the large distance from the Sun – is cold.”

source NASA.JPL

Leave A Comment